Language barriers always make theatre difficult. While many theatrical elements (such as dance and music) can transcend language, it’s hard to feel the full weight of a piece of theater when you don’t understand what the actors are saying. That being said, part of what makes theatre so magical is its ability to tell us the stories of people who aren’t like us, including those who don’t speak our language. So where is the balance? How do you honor the culture of the characters you’re portraying and still make the work accessible to local audiences? Like with most tough questions, there is no right answer.

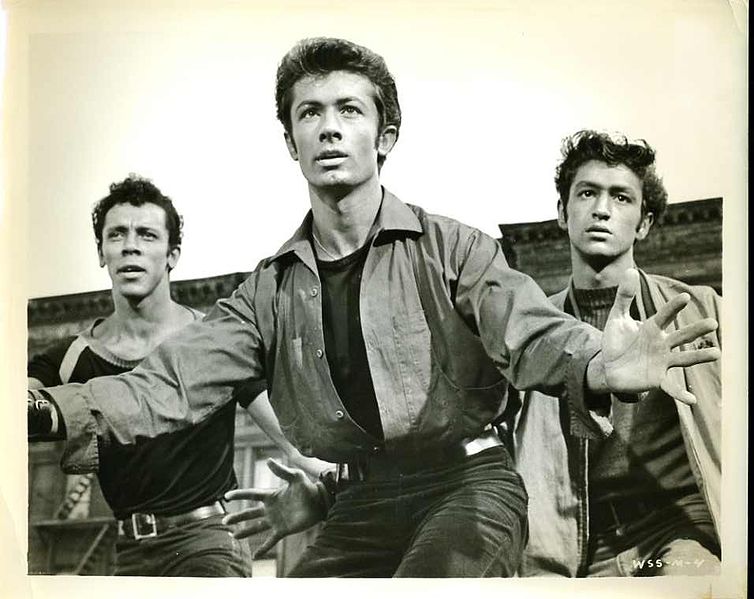

There have been several attempts throughout the years to integrate multiple languages into a theatrical performance, mostly aimed at Spanish speaking audiences. “In the Heights,” a Tony Award winning musical focused around a predominantly Latin community in Washington Heights, would use repetition of certain Spanish words and phrases such as “Paciencia y Fe,” “No Me Diga,” and “Alabanza” until the English speaking audience derived their meanings from context. A recent revival of “West Side Story,” a classic musical centering on a turf war between white and Puerto Rican gangs in New York, also integrated Spanish into its music and dialogue. Unlike “In the Heights,” “West Side Story” relied strongly on people’s familiarity with Sondheim’s classic lyrics to break the language barrier. Since people were so familiar with the musical (or at least with Romeo and Juliet, which it’s based on) it was easier for them to fill in the gaps and understand what the Spanish speaking characters were saying.

But the most recent (and perhaps the most effective) attempt to bridge the language barrier on Broadway is Deaf West’s upcoming revival of “Spring Awakening.” Deaf West is a theatrical production company based in Los Angeles who specializes in bringing deaf and hearing audiences together with performances that cater to both. They’ve received national acclaim for their productions of “Pippin” and “Big River,” but “Spring Awakening” is being heralded as their most inventive and emotionally effecting piece yet. Whereas Deaf West’s past productions have just set their stories in a universe where everyone magically knows sign language, director Michael Arden is making a more powerful statement this time by making only certain characters deaf. The result is that this production actually highlights the language barrier instead of trying to erase it. While the show uses several devices (including projections of spoken/signed dialogue) to make the story easily understandable to both hearing and deaf audiences, there are moments in the show in which only one language is used and the audience is forced to feel the frustration and confusion that the characters experience on a daily basis.

“Spring Awakening,” written by Duncan Sheik and Steven Sater and based off a 1891 play of the same name by Frank Wedekind, already addresses the communication divide between generations as children and their parents struggle to understand each other, so adding this language barrier heightens the effect (especially when one considers that roughly 90 percent of deaf people are born to hearing parents who literally can’t understand them). In a very real sense, this revival gives a voice to those who feel they have no voice of their own by making them silent. It also forces the audience to sit face to face with the effects of poor communication and stresses the importance to both the hearing and deaf community of accepting each other’s culture and working to promote intercommunication.

Since language is such an integral part of every culture, the language barrier will always be present in theater. But what productions show us is that this divide can be used as a tool to promote understanding of other cultures instead of as a hindrance to mutual understanding. For whether it’s a Puerto Rican Juliette, a Dominican bodega owner or a Deaf adolescent, their message is the same: listen to our story.