Black dancers excluded by limited costume options

February 18, 2019

In 2015, 54 percent of parents said their children were taking lessons in music, dance or art, according to the Pew Research Center. More than likely, some of those parents were struggling to find the right color clothing for their burgeoning performers.

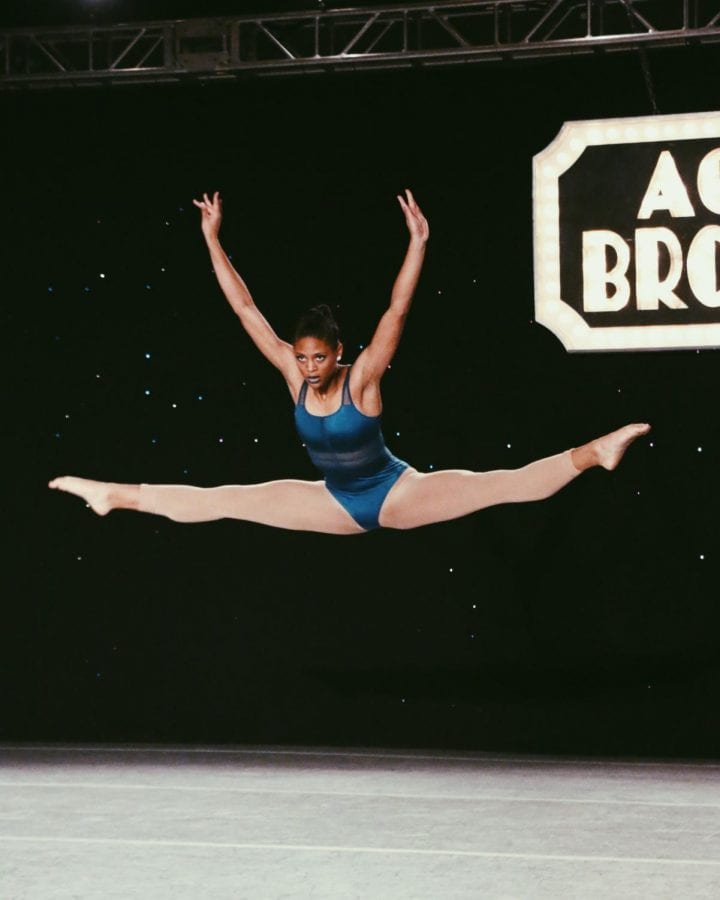

Desirée Wilkins, a sophomore majoring in theatre, knows her mom had to go “out of her way” to find the nude leotards, tights and shoes that Wilkins needed for shows. But when Wilkins had to start looking for dance clothes herself, she came to a realization: Companies just don’t make the nude shades needed for non-white skin.

“Doing shows in middle school is when I became fully aware and self-conscious about it,” Wilkins said. “My dance clothes were either way too light or way too dark.”

The experience of searching for variety and inclusion among racks of clothing has always been frustrating, Wilkins said. When Wilkins couldn’t find something close enough to her skin tone in a dance store or online, she felt ostracized.

“Especially as a kid, I constantly had the idea running in my head that I wasn’t like everybody else, and this only reinforced that,” Wilkins said.

Wilkins is not alone in her struggle to find clothing that works for her. Kenyata Nye, a postgraduate senior studying psychology, often felt bothered by the lack of diversity in dance clothes and the lack of understanding from her peers.

“I was the only black girl in my company, and there were many times I thought to myself, ‘Wow, I wish I was lighter,’” Nye said. “The other dancers would joke, like, ‘Oh, we stand out because you’re too dark for a nude leotard,’ and ‘OMG, what if Kenyata was lighter, then we would look like a group,’ because I honestly stood out that bad. The tights made me look ashy. The leotards were just hideous.”

Nye felt ignored by her dance teachers, who would disregard her concerns about finding clothing in the proper color.

“[They would] tell me I was overreacting, and never did they attempt to just order a dark tone leotard,” Nye said. “I guess they didn’t care.”

The conversation surrounding skin tone inclusion in retail has become more prominent since the establishment of Rihanna’s makeup company, Fenty Beauty. When Fenty launched its line of foundation, it immediately became one of the most inclusive on the market, boasting 40 shades.

The result was a rush of new lines from other brands, all trying to match Fenty’s popularity. Ulta and Revlon have started a new brand to offer a wider range of shades, and even Dior is dropping its prices and introducing a range of 40 shades.

But just because more variety is being introduced doesn’t mean that the problem has gone away. Zion Middleton, a freshman majoring in musical theatre, says he has to visit at least two stores every time he tries to buy makeup.

“I think it’s very important [for companies to include more shades],” Middleton said. “It allows the consumers to feel more appreciated and makes it much easier for them to get the products they need.”

As for Wilkins, the stress of finding clothing made with her in mind has lessened, but that’s probably because she’s gotten used to it over time, she said.

“Now times are slowly changing, which has led to a few better options here or there, but there’s still a long way to go,” Wilkins said. “I want to be able to walk into any dance store and find something that works for me.”

Nye’s problems were always more than finding the right color clothing. It was a matter of respect, she said.

“But I will say, I couldn’t take anything away from what happened, because I would have never learned to love me, along with the help of my parents, nor would I have been able to gain the ability to tell others who picked at me to STFU,” Nye said.