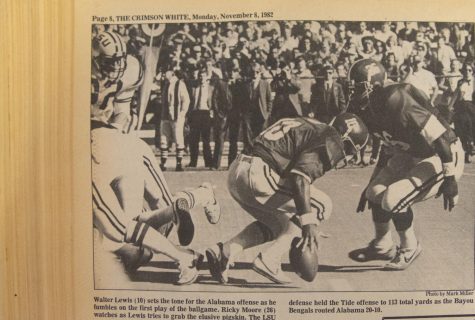

Timeline | Inside the Archives: How The CW covered race on campus

The news desk analyzes 100 stories across 20 years of integration and fights for diversity at the University.

The Crimson White news desk conducted an internal review of its coverage of race, cataloguing more than 100 stories published between 1954 and 1974. These 20 years saw some of the most important civil rights events in higher education, including the enrollment of Autherine Lucy Foster in 1956 and Governor George Wallace’s “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” in February 1963.

This review includes stories, letters and editorials as they were published. Editorials and letters, which do not fall under the same reporting criteria of journalistic integrity as published articles, nevertheless provide insight to the discourse around some of the most historically significant moments at the University.

One letter claimed that the NAACP was a Marxist organization bent on destroying America, a claim that detractors of today’s civil rights movements still pin on those who fight for equal treatment and justice under the law. On the page opposite to that was another letter, this one written by Tom Flintt Oko of Dublin, Ireland, filled with congratulations and excitement for the “unprecedented and noble behavior” of UA students during the enrollment of Vivian Malone Jones and James Hood.

1950s

In the two years immediately preceding Lucy’s enrollment at the University, The CW published three stories about the integration of schools. These stories, which portrayed overwhelming hesitance about desegregation, were the only ones that explicitly mentioned race throughout 1954 and 1955.

A story published in November 1954 maintained that “the color line will disappear” in accordance with the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education earlier that year.

“The colored people will be admitted to the University as students sooner than most care to think,” the story said. “If it must come, the gradual integration is to be desired rather than a sudden influx.”

About a quarter of the Feb. 7, 1956, edition was devoted to coverage of Lucy Foster’s first day of classes, in which her name was repeatedly misspelled as “Arthurine.” But it more closely followed the white student mobs that gathered across campus. The remainder of the edition is devoted to standard content of the time, like the “CW Society” page, which predominantly covered white Greek life, and ads for theater performances.

The following edition’s cover included two references to Lucy Foster’s enrollment. In a letter addressed to UA President Oliver Carmichael and his wife, the SGA expressed its “most sincere apologies to the distinguished couple” for the “great injustice” they had faced throughout Lucy Foster’s first week of classes. The second mention of Lucy Foster appeared in a recap of the SGA’s resolution “condemning mob action,” which stated that “the issue was no longer one of opposing desegregation but whether the University was to be ruled by a mob or by the administration.”

In that same edition, the CW published an interview with Carmichael about the status of Lucy Foster’s enrollment along with a series of letters from readers voicing their opinions on desegregating.

Four more stories about Lucy Foster’s enrollment were published before the end of the semester.

1960s

Seven years later, the CW reported on initial rumors of Vivian Malone Jones and James Hood’s intent to enroll as students and followed the story until their eventual enrollment on June 11, 1963. The next two weeks of CW coverage included about 20 stories discussing Malone Jones and Hood’s enrollment, including an editorial by James Hood and a pro-integration letter by Mississippi novelist William Faulkner, which he wrote when Lucy Foster first registered at the University.

Two days before their enrollment and Governor George Wallace’s notorious “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door,” The CW published a letter titled “Our Own Back.” In this piece, which claims no author, The CW argues for segregation on the grounds of states’ rights.

“The courts have ruled that integration must come, and segregation is illegal,” one part of the piece reads. “We disagree with these rulings on [a] states’ rights basis, although we are in favor of desegregation on moral grounds. We feel that, ideally, the state should have authority in matters concerning public education.”

By July, coverage of Hood and Malone Jones had virtually disappeared. Between early May and late June, there were 24 articles, editorials or letters covering the integration of the University. From July to the end of October 1963, there was one article on the topic. In that period, The CW dedicated more space to border conflicts between Malaysia and Indonesia than integration on campus.

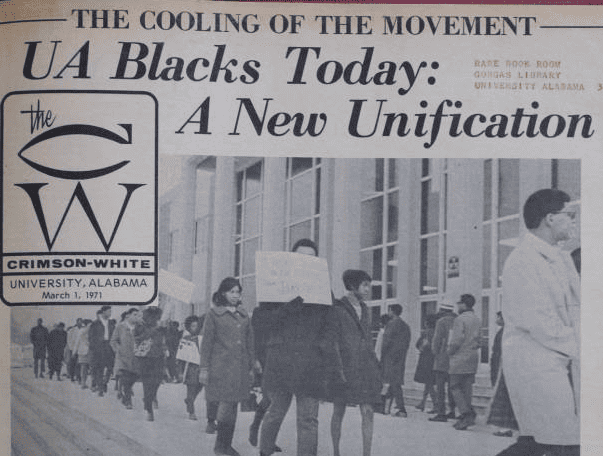

1970s

The year 1971 marked a transition in the CW’s coverage of Black students and Black student organizations. In that year alone, the paper published 36 articles, editorials or letters about Black students or Black student organizations.

The growth of the African American Association and its quest for the construction of an “Afro-American cultural center” was the CW’s most prominent source of coverage about Black students.

Black students held a sit-in at the President’s Mansion in late April 1971 to demand a Black studies program and improved working conditions for Black employees. Demonstrations continued throughout the next week, and demands morphed to include a center for Black students.

After negotiations with then-president David Mathews, the protestors left the Rose Administration Building, and the Student Government Association (SGA), an all-white student group, met soon after to discuss plans for an Afro-American cultural center.

“It is sad that force, no matter how non-violent, is necessary to change these times,” said Pete Cobun, The CW’s editorials editor at the time. “It is sad that blacks must demonstrate to gain equality and shake the institution to gain feelings of security at a white institution. But all these factors are factors of gradual change—a change SGA should hasten to realize and hasten to act upon.”

In October of that year, John Bivens, president of the African American Association, claimed that the SGA was intentionally stalling the bill that would fund and establish the cultural center. The following week, the bill was withdrawn before it could be voted on.

A CW editorial titled “Reconsider the Black Man” urged the SGA to approve the Afro-American cultural center. “Reconsider the Black Man” argued that if the Afro-American cultural center wasn’t funded, there would be violent protests and riots. The coverage of the African American Association’s attempts to secure the Afro-American cultural center was chronicled by the CW as it related to the SGA.

Days after the bill was withdrawn, the African American Association had raised enough money independently to run the Afro-American cultural center without the SGA or its oversight of the facility. In February 1972, the newly opened cultural center was dedicated to Malone Jones.

Even though much of the coverage revolved around protest and conflict, 1971 still saw more articles about Black students than any other year reviewed. Over the next two years, 16 articles would feature Black students. Seven were written outside of Black Heritage week.

In 2010, Malone-Hood Plaza and the Autherine Lucy Clock Tower were dedicated at the location of Governor Wallace’s infamous “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door.”

Today, the spot of the former Vivian Malone Afro-American Cultural Center is an empty lot next to Publix on University Boulevard.