‘Moving the needle’: Tuscaloosa women are ready for a seat at the table

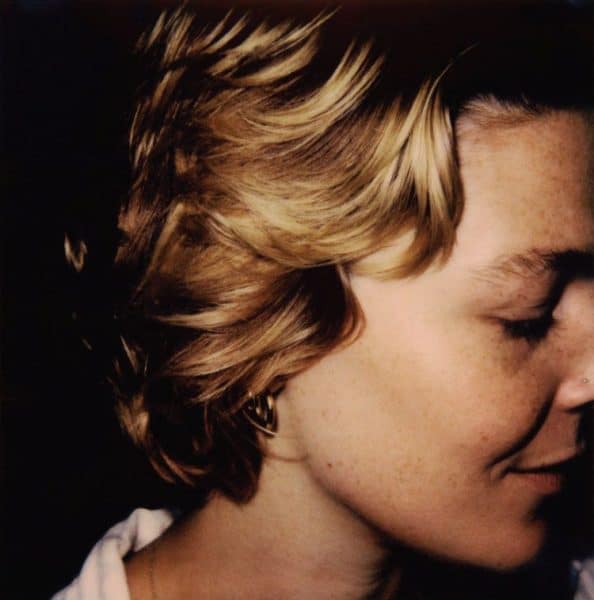

Serena Fortenberry and Katherine Waldon are ready to go to work for their communities.

March 1, 2021

As only the third woman to run for mayor in Tuscaloosa history, Serena Fortenberry has been repeatedly underestimated and undermined by her colleagues and her community. Regardless of their party or politics, Alabama women in local government have been facing these challenges for years.

Fortenberry said a Tuscaloosa businessman told her he is supporting her mayoral campaign because she thinks like a man, not a woman.

“I responded, ‘No, I think like a woman,’” she said.

Fortenberry was unperturbed as she recounted how she’s also been asked by a man if, should she be elected, she would wear dresses or pantsuits.

“I’ve sat in a lot of committee meetings where I was one of maybe two women, and the rest of the room was men,” Fortenberry said. “Definitely, I have felt the effects of mansplaining or, you know, felt that I was somewhat dismissed because of a presumption that I didn’t know as much as my male counterparts.”

But Fortenberry’s experience isn’t isolated. By all accounts, women in Tuscaloosa politics encounter sexist behavior on a daily basis and know they are not always taken seriously, but they try not to let that deter them.

Katherine Waldon, one of three candidates for the Tuscaloosa City Council’s District 1 seat, has degrees in political science and public administration, works as an English teacher in the Tuscaloosa City Schools system and founded a free summer enrichment program for young students.

Yet, being a wife and mother, the question Waldon said she’s asked most is, “How are you going to do it all?”

“Of course, how I want to react is [by saying] that we don’t ask male candidates that,” Waldon said. “You know, they can have jobs, they can be husbands and fathers, and that’s not the first question people ask…Women can do what men can do.”

Waldon and Fortenberry, who live in District 1, are both political newcomers whose campaign goals are strongly rooted in their personal experiences as residents of Tuscaloosa and their shared district.

Both women are concerned about the city’s infrastructure, public safety and the current lack of transparency between city leadership and the public.

Waldon hopes to lower the city’s crime rate by addressing poverty, unemployment and education issues, in honor of her brother-in-law, who was murdered in a 2014 robbery.

For Fortenberry, her focus on city planning, operations and budgets ignited after she successfully combated a 2017 rezoning proposal for land near her home.

Fortenberry didn’t opt to run for public office in 2017, a decision which she has said she deeply regrets.

“I’m very proud that we have a city council that currently has four women on it – that’s wonderful,” Fortenberry said. “At the same time, though, it seems like we have such competent women in our city, such well-educated women who are very active in the community, and yet, I’m only the third woman to run for mayor in the city of Tuscaloosa. So that’s a little bit of a sad commentary.”

Fortenberry’s predecessors are Judy Moody, who was defeated by Ernest Collins in the runoff of a 1976 special election following Mayor Snow Hinton’s death, and Sarah McBroom, who made an unsuccessful bid for mayor in 1997. Before her mayoral campaign, McBroom served as the first woman on the Tuscaloosa City Council, a position which she held for eight years.

For the last 20 years, however, the seat has yet to see a female candidate.

The incumbent, Mayor Walt Maddox, has held the seat since 2005.

“One big obstacle to women’s equal representation in politics is the fact that they are much less likely to run for office,” said Regina Wagner, a political science professor at The University of Alabama. “Now, part of the reason for that is that women themselves still often feel like they are not prepared or qualified to run. Research has shown that women need more encouragement to run for office than men do. For the most part, when women do run, they are about as likely as men to win, but they run much less often.”

Wagner said women may be discouraged, in part, because of inconsistencies between the treatment of male candidates and that of female candidates. Women receive more scrutiny for their appearance and demeanor, and historically, have had to work harder to prove their qualifications.

While Fortenberry hopes to make history in Tuscaloosa this year, other Alabama women have been fighting similar battles for years.

In nearby Northport, Donna Aaron, who just finished her first term without seeking re-election, served as the city’s first female mayor from 2016 to 2020.

Gov. Kay Ivey became only the second woman to serve as Governor of Alabama when her predecessor, former Gov. Robert J. Bentley, resigned. Ivey, who was Lieutenant Governor of Alabama at the time, assumed the position, before being elected to a full-term in her own right in 2018.

Alabama is actually statistically ahead of other states in female gubernatorial representation.

According to the Center For American Women And Politics (CAWP), Alabama is one of only nine states with a female governor currently in office. There are still 20 states in which a woman has never served as governor, and only in 11 states have multiple women served as governor.

Yet, the representation of Alabama women in local government is entirely different.

According to the CAWP, as of June 2020, only 23.3% of the mayors of U.S. cities with populations over 30,000 were women. Only one of the mayors on that list represented a city in Alabama.

“I think sometimes, particularly maybe in the South where we are more traditional in our family structures, where we have some long-standing sensibilities about domestic roles, it’s a little bit of an uphill battle for a woman to seek a leadership position successfully,” Fortenberry said.

But Fortenberry’s candidacy is a tenacious defiance of those preconceived notions about women’s roles and capabilities.

She is a wife and mother of three in addition to her full-time job as an English professor at UA, but she still has had time to belong to more than five community committees, serve in elected positions as a member of the UA Faculty Senate and as vice president of Tuscaloosa Neighbors Together, organize the Newtown Neighborhood Association and now launch a mayoral campaign.

Despite the challenges of being a female candidate, is determined to use her platform to effect change in Tuscaloosa. Reducing spending, making drastic changes to infrastructure and city planning and increasing transparency within city hall are at the core of her agenda, with the backing of other women helping her get there.

“Most of my donations to my campaign have come from women, so there’s this wonderful network of female support,” Fortenberry said. “I have gotten donations from women who live in other cities, women whom I haven’t seen for years who I graduated high school with and women that I went to summer camp with long ago, so that’s so fantastic to me that there is such enthusiasm among women to see another woman seek a leadership position.”

Meanwhile, for Waldon, the support and inspiration come from her daughter and female students.

“We [women] definitely aren’t seen as a gender that can effectively run for office and make good decisions for a body of people,” Waldon said. “But I do believe that we are trailblazing forward, moving the needle and hopefully setting the pace for many other young women to come.”