‘It’s so much more than just an image’: UA alum Alayna Pernell works to give restorative justice to Black women in a new photo series

July 25, 2021

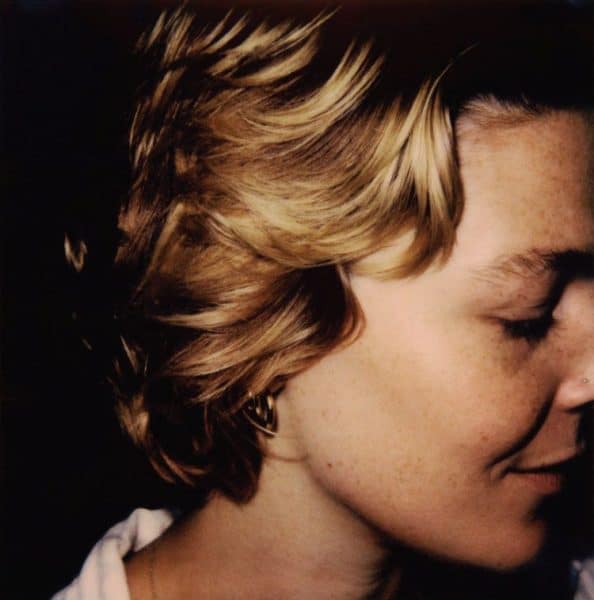

Alayna N. Pernell, a 2019 UA alumna who holds a bachelor’s degree in studio art with a concentration in photography, knew she wanted her work to make an impact. It wasn’t until she began her Master of Fine Arts in photography at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago that she saw just how big of an impact her images could have.

While at The University of Alabama, Pernell’s style was abstract and metaphorical. She shot objects and places that represented her feelings about her life and the world itself. Toward the end of her junior year, she began creating portraits and self-portraits. However, it wasn’t until she started studying photography at SAIC that her work became more sociopolitical.

Although she received several acceptance letters from different graduate schools, Pernell knew that Chicago was where she wanted to pursue her career as a photographer.

She said she wasn’t expecting the city to feel like home, being from the small town of Heflin, Alabama, but now it’s hard for her to imagine living anywhere else.

Chicago was where Pernell began doing what she calls “restorative justice work,” a theory that describes a certain response to wrongdoings; the response usually involves meetings between the victims of crimes and the offenders to reach an agreement on restitutions that can be made.

Previously, at the Art Institute of Chicago, Pernell had come across a collection of more than 900 photographs of women in various sepia and monochrome tones. These had been incorrectly labeled as belonging to Peter Cohen, an art collector in New York City.

Pernell was deeply troubled by the AIC’s website listing Cohen as the “artist” behind the collection, thereby implying he was the photographer when he wasn’t.

After Pernell reached out to Cohen via email to voice her concerns, Cohen promptly contacted the curators at the AIC to correct the error. Each photograph on the website is now listed as having an “Unknown Maker.”

While viewing the photographs, Pernell had been particularly drawn to the Black women in them. With help from Cohen, she has since made it a priority to try and trace the origins of the photographs so she can learn the women’s identities and give them back their names.

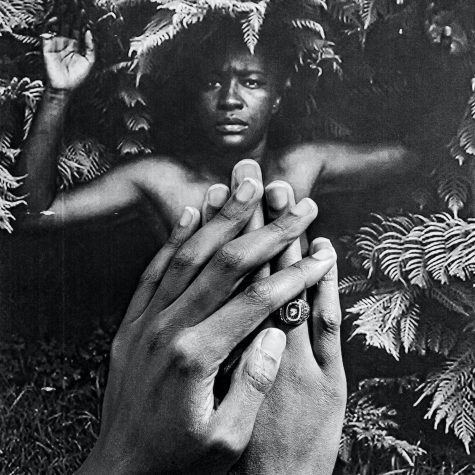

Eventually, the images of the Black women became the inspiration behind Pernell’s work. Her most recent series of photographs, “Our Mothers’ Gardens,” pays homage to the women featured in the images collected by Cohen and was awarded the 2021 Snider Prize by the Museum of Contemporary Photography.

“The basis of my inspiration was looking at representation and thinking about why certain images aren’t talked about in an honest way and how harmful that can be,” Pernell said. “It’s so much more than just an image. I look a lot at how women are represented, especially Black women.”

According to Pernell’s artist statement “What They May Not Tell You,” “Our Mothers’ Gardens” explores the history art has with capturing and studying the bodies of Black people, specifically women.

“Black bodies have continued to be seen as objects to capitalize on and oftentimes hardly anything beyond that,” Pernell said in the statement.

The title “Our Mothers’ Gardens” was inspired by Alice Walker’s “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose,” a text in which Walker “talks about her search of the African American woman’s suppressed talents and skills that they lost because of slavery and a forced way of living.”

With these ideas in mind, Pernell was particularly intrigued by Maudelle Bass, a professional dancer and one of the first women she ever researched, who was the subject of her piece “With Care to Ms. Maudelle Bass Weston.”

Edward Weston, an American photographer, took the original picture Pernell used of Bass. Pernell thought it was disturbing how Bass looked uncomfortable in all of Weston’s photographs. In Weston’s monochrome photograph, Bass stands against foliage, completely nude, her hands raised with a grimace on her face.

“In none of the images did she look settled. I did more research and found things [Weston] had said about her prior to photographing her. They were really derogatory. It just felt exploitative. Her story became very important to me,” she said.

After a while, Pernell realized that in order to combat and correct that exploitation, she needed to be closer to her subjects and handle them with intimacy and care. This is where the significance of her hands came into play, specifically, the idea of skin-to-skin contact.

“I kept looking at the images, and I felt like I needed to be closer to them,” Pernell said. “I thought, ‘How can I show this protection and this care?’ In my mind, that skin-to-skin contact is so intimate and vulnerable.”

In Pernell’s version of the photo, “With Care to Ms. Maudelle Bass Weston,” she uses her hands to cover Bass’ frontal nudity, placing them one over the other in an almost protective fashion. It’s as though Pernell, acknowledging Bass’ discomfort, is protecting her body — and thus her humanity — from prying eyes.

This was what “restorative justice work” meant to Pernell: being able to work with Cohen and his collection to further the conversation surrounding the exploitation of Black women in art. She emphasized in projects like this that collaboration and mutual understanding are important in correcting past injustices.

“I don’t like to present my work in a way that’s like, ‘Here’s the issue. You fix it,’” she said. “It’s more, ‘Here’s the issue. Let’s talk about how we can correct it, moving forward collectively.’ We need to hear each other out.”

This personal connection to her work is why she was “shocked” when she found out that she won the Snider Prize. She said she didn’t realize that her work would have such a large impact on people.

“When it was publicly announced and shared, it felt like the issues I was talking about in my work were finally being seen,” she said. “I felt very grateful and appreciative that I could bring attention to something that’s really important to me.”

In recounting what it was like to win a major award, Pernell described the biggest challenges that come with being a photographer.

“It’s getting both respect and recognition,” she said. “It’s hard because photography’s a small world, and it’s cutthroat. It’s only been around for about a century, so it’s still fairly new. And with people creating more contemporary work like I am, it’s difficult because it’s often seen as something that anyone can do.”

While on the topic of recognition, Pernell offered valuable advice for young artists wanting to make careers for themselves.

She stressed that, first and foremost, it’s important for artists to care about what they’re creating. She discouraged creating art solely to receive recognition or prove people wrong, stating that an artist’s work should matter to the artist before mattering to others.

“Your work will always speak for itself,” she said. “If you care about it, then other people will care about it. If you don’t care about it, then people will definitely recognize that, and that will cause issues down the road.”

Pernell also emphasized the importance of persistence.

“Just keep trying,” she said. “Ask people for help, especially professors or people you’re close to. Someone is always willing to help. Send that email. Send that application. Don’t set yourself up thinking that someone will say no or your application will be rejected. You could be cutting your chances of something really great happening.”

Now, after graduating from SAIC last spring, Pernell has taken a slight hiatus. However, those interested can still receive updates about her art through her Instagram and website, where the rest of her collections can also be found.