Opinion | It’s time for UA to recognize its queer past

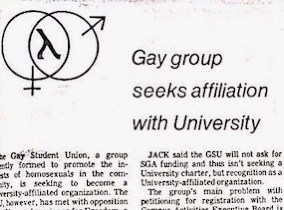

A cover story in April 1983 reports the controversy surrounding the establishment of the Gay Student Union.

October 31, 2021

When we honor diversity and inclusion on this campus, I’ve always felt ambivalent about the way we celebrate heritage months. As president of Capstone Alliance — the only LGBTQ faculty and staff organization at this University — I am both grateful for the events that promote LGBTQ history every October and dissatisfied that these events are confined to one month. As we close out LGBTQ History Month and our attention drifts elsewhere, it is worth remembering one historical event in particular: the founding of the first gay student organization at the Capstone in the early 1980s. As we strive toward greater inclusion, it is time for the University to recognize this queer story as a campus story.

Creating a Gay Student Union on The University of Alabama’s campus was not as straightforward as it seemed. As the president of the GSU explained to The Crimson White on Feb. 2, 1983, they were required to submit the names and addresses of the officers in addition to the names of at least 10 members to the Campus Activities Executive Board. This was a problem for some members, who feared that public display of information would out them to their parents and employers and expose them to “possible harassment and violence.”

Even the faculty adviser was reluctant to release his name publicly, instead conveying anonymously that he would “expect students to be open-minded” about the GSU. Summing up this dynamic, the president of the GSU, only going by “Jack” in the article, stated emphatically, “We’re not scared. Cautious is the word. But caution is good in any aspect of life.”

Indeed, the degree of caution exhibited by the members of the GSU may seem bizarre from our vantage point. In our present day, same-sex marriage is legal in Alabama. The Supreme Court has ruled that employees are protected from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. And according to the Pew Research Center, 72% of surveyed Americans say homosexuality should be accepted by society, which is 21 points higher than those surveyed when Pew first asked the question in 2002. This shift in attitudes and laws over the decades has made the United States a more welcoming place for LGBTQ people.

However, this was not yet the case in 1983. Students rightly feared rejection by their parents and peers, the loss of financial backing from families and employers, and the violent harassment of onlookers who resented their expression of authenticity. The legitimate concerns that GSU members felt and the tremendous resolve required to declare themselves members of a despised group make them worthy of the campus slogan, “where legends are made.” Yet you would be hard-pressed to find an official reference to these legends anywhere on the University’s website. Based on my own conversations with current students, the history of the Gay Student Union is hardly known at all.

The absence of historical knowledge on this topic is even more alarming considering that many LGBTQ students continue to experience rejection, financial strife and violent harassment in their own coming-out process. Although there has been tangible progress in achieving LGBTQ rights overall, these issues continue to impact students, and our lack of historical understanding enables a complacency that is harmful. If today’s students had a better understanding of the history of the GSU’s founding, they would be able to distinguish the similarities and differences between these times, and realize what still needs to be changed. Learning about this history would allow LGBTQ students to draw strength from the example of these early pioneers. The fact that these GSU members dared to come together and advertise their plans to become a campus organization should be considered bold.

That boldness triggered an explosion of debate across The Crimson White’s pages. An initial letter to the editor on Feb. 9, 1983, described homosexuality as a “sickness” and claimed granting the GSU a charter would “downgrade the University.” A week later, three more letters were published, condemning the initial letter for stigmatizing gay people. One of those letter writers argued that granting a charter would “demonstrate that the University has advanced from its legacy of denying civil rights.” The letters addresed the removal of homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association’s list of mental disorders nearly a decade prior to reinforce that gay people weren’t the problem, but rather that prejudice and closed-mindedness were.

As February turned to March, the arguments devolved into whether homosexual “lifestyles” were morally tolerable and if granting a charter meant the University was sanctioning degeneracy. Two senior students scoffed at the prospect of the GSU getting funded through tuition dollars.

“How would you like to call home to say, ‘Mom, Dad, congratulations. You just contributed to an organization that approves of homosexual behavior,” the students wrote.

The president of the GSU later changed course and pursued recognition instead of a charter so that they couldn’t apply for SGA funds, but the idea that the University was even tacitly supporting the rights of gay people to visibly organize and express themselves became a fixation for GSU opponents.

That opposition coalesced into a petition circulated by Young Americans for Freedom, a conservative student group that strongly resisted the recognition of the Gay Student Union. Infusing their arguments with disinformation, they clamed in their petition that “a homosexual group at The University of Alabama would threaten the civil rights of minors,” and that since sodomy was illegal in Alabama, the “official recognition of a group that advocates such behavior would encourage the violation of laws of the state.” These claims, outrageous and harmful on their face, invoked the homophobic trope that gay people “recruit” children through sexual abuse and equated speaking about gay rights with promoting sexual acts.

Unfortunately, these attacks forced the Gay Student Union into a defensive posture. The president of the GSU, still going by “Jack” to avoid harassment, responded to YAF mudslinging by saying, “We deal only with people over the age of 19. The GSU is not out to corrupt or recruit anybody.” Whether debunking these absurd arguments was necessary or not, debating on YAF’s terms did not quell the accelerating controversy. After petitioning the University for official recognition in April of 1983, the Campus Activities Executive Board dealt a blow to the GSU. They required a new group of officers to undergo a lengthy orientation process, ensuring that the GSU’s application for recognition would be delayed to the fall semester. YAF’s tactics of fearmongering had succeeded in derailing the charter approval process.

At this point, the only way for the Gay Student Union to move forward was to play offense. Writing to UA President Joab Thomas, English professor David L. Miller, the GSU’s faculty adviser, laid out what was at stake. By this point, Miller had shed his initial anonymity and was a vociferous defender of the GSU in the editorial pages of The Crimson White. In his letter to Thomas, Miller said the GSU was in consultation with the American Civil Liberties Union and the Office of University Counsel, which both concluded that the University had a legal obligation to recognize the GSU.

Framing the recognition of the GSU as an inevitability, Miller’s subtle threat of a lawsuit was backed by the arrival of another letter to Thomas the next day from the ACLU. In its letter, the ACLU sought to dismiss any notion that slowing down the GSU’s application would make the issue go away, stating, “Here as elsewhere, justice delayed is justice denied. … Any unnecessary delay would have to be understood as, in effect, unfavorable action on the merits.”

The GSU had to wait until the Campus Activities Executive Board reconvened at the beginning of the fall semester. Although the GSU met all of the procedural requirements for recognition, the CAEB listened to the objections of YAF and denied the GSU’s petition.

This decision was immediately overruled by Melford Espey, the director of campus activities, who said that if any organization that petitioned for recognition met all of the requirements, it would be recognized by the University regardless of any pressure from student groups. Thomas later acknowledged that legal precedents were on the GSU’s side, and that granting recognition was preferable to lengthy and costly litigation. The GSU’s triumph infuriated YAF, who tried to appeal to the board of trustees, but the board, too, sided with Thomas and his assessment.

The GSU had a successful run throughout the 1980s, advocating for acceptance and building community. Over the years its name would change to reflect their inclusion of more sexualities and gender identities, from the Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual Alliance to the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Alliance to what we now call Spectrum. The organization that I represent, Capstone Alliance, honors the legacy of the Gay Student Union by naming our annual scholarship after “Jack,” whom we now know as Elliot Jackson Jones. The story of Spectrum and its founding, with the brave students and professors standing up to the powerful forces of hatred and ignorance, inspires us as LGBTQ employees at this university.

This inspirational tale is only known to the handful of people who happen to come across it. Even though the controversy over recognizing the GSU dominated headlines in 1983 (the story was second only to the death of Alabama head coach Paul “Bear” Bryant earlier that year), students today would not be able to recite this history. As we near the end of October, which the University has acknowledged as LGBTQ History Month, this problem begs the question: Why isn’t the founding of the first gay student organization officially considered a campus touchstone, integral to our understanding of the University’s past?

When it comes to the University’s strides toward inclusion, there are other historical events that are considered campus touchstones. The most obvious example is the racial integration of the University, first unsuccessfully with Autherine Lucy in 1956 and then successfully with Vivian Malone and James Hood in 1963. Another is the enrollment of women at the Capstone, with Bessie Parker and Anna Adams being the first admitted female students thanks to the lobbying efforts of Julia Tutwiler. These moments deserve to be lauded as landmark events where the University moved toward greater diversity, equity and inclusion.

But where is Elliot Jackson Jones in our university’s history? Where are the other students who fought for a Gay Student Union? Where are David Miller and the dozens of faculty members who co-sponsored the GSU? Their names deserve to be part of the campus story that we all tell ourselves.

Initiatives like the Summersell Center are a great way to start telling these stories, but there are so many stories to be told. Even beyond the founding of the GSU, there are tales of transgender students and gender-nonconforming students fighting for recognition and acceptance. There are stories of same-sex couples looking for legal status and advocating for the joint benefits they deserve. There are members of fraternities and sororities, struggling to come out as their authentic selves, whose narratives deserve to be included.

In a letter that was kept in the GSU’s archived records, a 19-year-old student anonymously writes that he has been following the efforts of the organization through The Crimson White’s coverage and commends them for their efforts. He writes that he recently admitted to himself that he is gay, but that he is closeted to everyone he knows, even his friends and family. He concludes the letter with only his P.O. box and a simple request: “I am writing this letter in hopes of speaking to someone like myself, if possible.” Honoring LGBTQ history on our campus means closing the gap between that student then and students like him today.

We look toward history to make meaning of our lives and find someone or something that resonates with our own truth. While the University is now recognizing the importance of events like Stonewall, LGBTQ history is not external to the borders of Tuscaloosa. That history is right here, and it deserves to be lifted from the shadows. Whether through sponsoring lectures, creating more classes or establishing a historical commission, bringing this history to light requires investment and dedication.

We know our campus history is queer. I am asking for the University to finally come out to itself.