Accountability: Protecting Alabama’s Waterways

June 8, 2022

Just over three years ago, piles of dead fish lined the edges of the Black Warrior River. A sign of its uninhabitable conditions, 200,000 fish and other wildlife were killed as the water carried a sheen across the surface and distinctly pungent smells. Something had spilled into the water, but the source was not clear.

It was about a week before the Alabama Department of Emergency Management reported any tangible results. They measured extreme levels of E. coli contamination on the day of the fish kill, but hesitated to publicize their findings, creating a separate controversy.

Meanwhile, Tyson Farms issued a public warning on June 7 to “avoid recreating in Dave Young Creek or the Mulberry Fork until further notice.” They had spilled 220 thousand gallons of anaerobic wastewater, rendering the next 50 miles downstream unusable. Though the cleanup costs would be just as gargantuan, Tyson Farms escaped the incident with a $3 million settlement.

Incidents like this are all too common in the Black Warrior River. In June 2016, just three years before Tyson’s spill, the same area experienced a smaller fish kill from waste pollution.

These both came after the Black Warrior River was labeled among America’s 10 most endangered rivers by American Rivers in 2011. The Southern Environmental Law Center attributed this to mining pollution, noting it affects drinking water in the process.

As pollution continues to plague the Black Warrior River, it becomes increasingly important to ask where this damage comes from, the extent to which it affects Alabamians, and what can be done to prevent it in the future.

“Keep on a-mining, boy, ‘cause that’s why you were born”

The Black Warrior River’s largest threat comes from coal. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has allowed some 95 coal mines to operate on the watershed. Using the Nationwide Permit, these mines minimally account for water conditions or potential public impact of their operations.

Across Appalachia, this practice is largely restricted. Alabama, however, is the sole exception that destroys water and wildlife, per Gerrit Jobsis, American Rivers’ Southeast Regional Director. As such, dangerous practices uniquely plague Alabama’s waterways, threatening one of the state’s most prized assets.

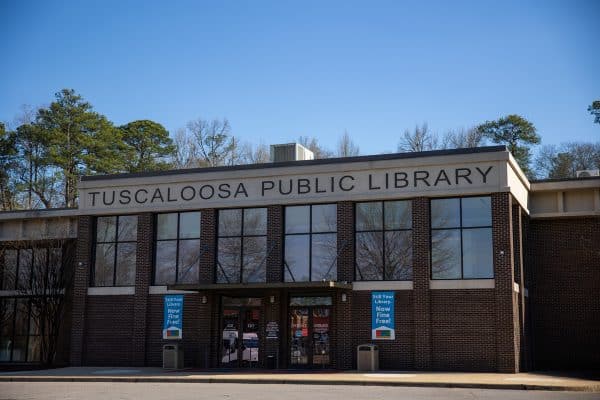

On May 3, creeks in Tuscaloosa County turned black from coal pollution, rendering more of the river uninhabitable. Nelson Brooke of the Black Warrior Riverkeeper attributed the discharged wastewater to Warrior Met Coal’s Mine #7 in Brookwood.

Texas and Davis Creek in Tuscaloosa County were dyed black from coal spills

Photo by Nelson Brooke, Black Warrior Riverkeeper

In an email sent to ABC3340, a spokesperson for Warrior Met Coal mentioned that they had “not been informed of any non-compliant water samples.” Nine days later, the Alabama Surface Mining Commission issued a notice of violation. So much for that “99.8% compliance record” that they boasted.

Near Birmingham, the Drummond Company is just now reaching action after acid mine drainage from the Maxine Mine was illegally discharged into the Black Warrior River for over 42 years. Their fine? 3.6 million dollars.

But the impacts on citizens are troubling. Exposure to coal ash alone is linked to a number of dangerous health problems, including heart damage, cancer, reproductive problems and various neurological disorders. The Black Warrior River is a source of drinking water for cities like Birmingham, Bessemer, Cullman, Jasper, Oneonta and Tuscaloosa, extending the risk to millions.

Then there are other pollutants. The 1972 Clean Water Act aimed to eliminate all point source discharges by 1985, but there are more now than ever. Despite dumping unknown pollutants into the water, the Alabama Department of Emergency Management issues permits for point source discharges while failing to regulate them.

Since 2000, other facilities have been caught dumping methane gas, raw sewage and mercury into the water. Miller Steam Plant notably dumped the most mercury of any coal-burning power plant in the nation in 2007, making fish from the Black Warrior River contain methylmercury.

I collected random survey responses from 85 students, measuring their perception of cleanliness in Alabama’s waterways. The raw data can be found here. Given the low sample count, it’s best to take these results anecdotally, but the responses send a clear message: be wary of the water.

A majority of respondents (60%) recreationally used West Alabama’s water sources in the past year, but it’s safe to assume the Black Warrior River is not among that group. Only 10 respondents agreed that the Black Warrior River was clean enough to swim in, with a large majority expressing either disagreement (27) or strong disagreement (29).

The results are more damning when asking whether respondents are “concerned about the effects of pollution in the Black Warrior River.” Nearly every person indicated either agreement (16) or strong agreement (58) with the claim, with only two people indicating disagreement and none expressing strong disagreement.

It’s no wonder the Black Warrior River is among America’s most endangered rivers. As industries continue to engage in dangerous waste practices, though, the threat shifts to Alabama’s citizens.

Many cities along the river source their drinking water from it, risking exposure to coal ash among various other dangerous pollutants. If the fish weren’t already killed by the most recent dump, eating them can cause mercury exposure. Even swimming in the water can be dangerous at times.

Preventing Future Damage

These instances of neglect don’t happen in isolation. They are, instead, the result of decades of lax enforcement. Though pollution comes from industrial farms, sewage dumping, coal mining and quarries, the Alabama Department of Emergency Management often remains silent about the damages of these practices, and subsequent deaths of wildlife. When they impose fines for drastic damage, they often undercut estimates and citizen wishes.

So the effort has shifted to the advocacy sphere. The Black Warrior Riverkeepers track and report damages done to the river, seeking to protect and restore the area. They offer a number of ways for students to work on preventing future damage.

“Black Warrior Riverkeeper has a wide variety of volunteer opportunities for any undergraduate and graduate students at The University of Alabama,” said Charles Scribner, the Black Warrior Riverkeeper’s executive director. “Anyone interested in learning how to assist our clean water advocacy, whether through litter cleanups, social media outreach, pollution monitoring, or structured internships — and getting service credit through Bama Pulse for their volunteering — should email me at [email protected].”

Legal groups, like the Southern Environmental Law Center, take on cases that the Black Warrior Riverkeeper exposes. The SELC’s most recent case on the Drummond Company’s coal pollution is a major win for Alabamians. Their lawsuit, centered on Maui v. Hawai’i Wildlife Fund (2020), strengthens interpretations of the Clean Water Act on coal mine sites.

There’s a long way to go before the Black Warrior River is in good condition. Decades of dangerous policies and practices have, in many ways, devastated the region and its inhabitants. However, as legal, scientific, and advocacy groups continue to achieve victories, there is an emerging path for citizens to trump corporate greed and hold polluters accountable.