Opinion | Sports injuries are not entertainment

September 1, 2021

Alabama opens its season against Miami on Saturday. Going to a school that focuses so much on football, there is never a dull weekend. However, as sports like football, hockey and others start their seasons, some might wonder what makes physical sports so popular.

There is an innate tribalism that comes with being a sports fan: “My team is better than your team,” “My players are faster than your players,” and “My players hit harder than yours.”

We get excited when our favorite offensive tackle makes a great hit, as if we were somehow involved. Is the violence of sports something we like? And if that is the case, what does that say about the way we consume sports? Do we enjoy seeing people get crushed simply for our own enjoyment?

There is a growing conversation about how sports fans, and even sports writers, treat athletes. Because sports are a form of entertainment, it is easy to get wrapped up in the idea of athletes existing just to play for the enjoyment of others.

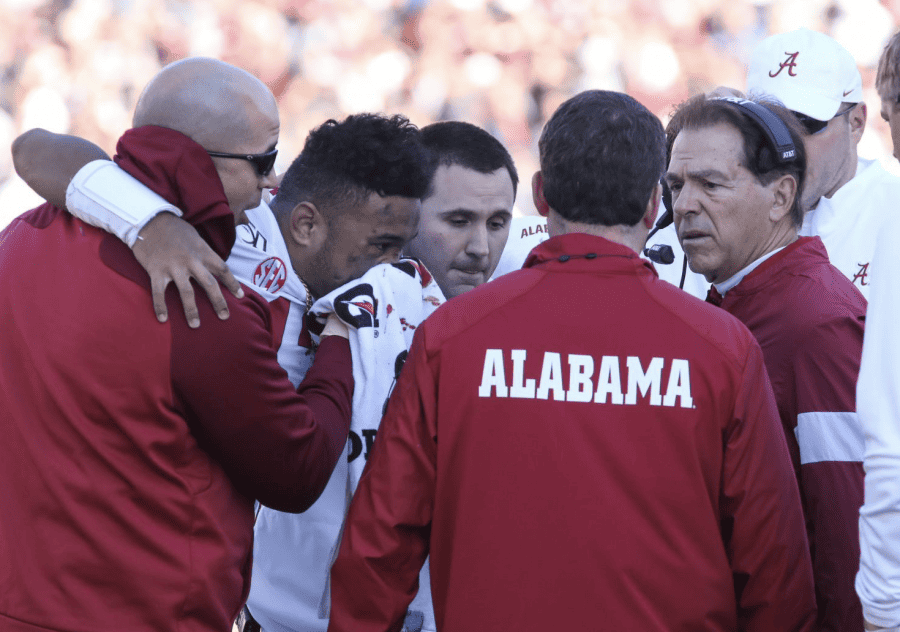

It’s easy to forget that while athletes are entertainers, they’re also real people and are vulnerable to injury. This is evident in the way violence is covered in sports media.

The consideration of violence in the media is not a new one. An age-old question among concerned citizens is whether media violence perpetuates violence in real life. Even the desensitization to violence caused by the media may be harmful.

Between vivid replays of violence and a focus on how injuries affect a sports team’s ability to succeed, the health of players is disregarded. As viewers, we all eventually become desensitized to seeing people injured, accepting injury as a normal part of consuming entertainment.

This desensitization can have lasting effects on viewers.

“Other research has found that exposure to media violence can desensitize people to violence in the real world and that, for some people, watching violence in the media becomes enjoyable and does not result in the anxious arousal that would be expected from seeing such imagery,” the American Psychological Association said in 2013.

It is important to remember that your favorite athlete has blood, bones and flesh just like you, and those things will break and bend in ways that it should not. When injuries happen, it’s not entertainment; it’s a concern that must be addressed. Giving athletes the grace to get hurt and heal is necessary to prioritize athletes as individuals.

With this grace comes the opportunity for athletes to speak candidly about their struggles. Over the summer, both Olympic gymnast Simone Biles and tennis star Naomi Osaka brought attention to how mentally taxing it is to be a professional athlete. It was not only a watershed moment for athletes, but also for Black women who are finally prioritizing their own health.

This attitude is not just found in the Olympics; it’s reflected on our own campus. Najee Harris, former Crimson Tide football player and current rookie Steelers running back, hopes to make a big impact in the coming NFL season.

When Harris is covered in the media, the focus is always on his previous injuries and how they could harm the Steelers’ offense in the long run. The main concern is how he is helping the team and not the possibility that he feels pressure to play through pain. He is expected to risk his health for the hope of victory.

When you see someone get hurt, is your first instinct to worry about the person in pain? Or is it to wonder if your team is going to stay undefeated? If you truly want to support your favorite team, start valuing the players and their health. For those who value the Crimson Tide, these questions are critical.

Caring about sports is a way of life, and everyone should be able to cheer, cry and celebrate their teams, but they also must remember that no one likes that person on Twitter telling athletes to “suck it up.”